|

Scientists find weakness in deadly fungus |

|

January 8, 2018 |

|

| Photo by Daniel

Lindner, U.S. Forest Service |

| A little brown bat being checked

for deadly white-nose syndrome. |

|

A team of scientists studying a fungus called

Pseudogymnoascus destructans, or P.

destructans, noticed something interesting:

it lacks a key DNA repair enzyme.

P. destructans

is the fungus that causes

white-nose syndrome (WNS), a disease that has

killed millions of hibernating bats in North

America in the past decade, including North

Idaho, and for which, so far, there has not been

a successful treatment.

|

| Photo by Brian

Heeringa, U.S. Forest Service |

| Little

brown bats hibernating. |

The discovery prompted Jon Palmer and Dan

Lindner of the U.S. Forest Service's Northern

Research Station and their partners, Kevin P.

Drees and Jeffrey T. Foster of the University of

New Hampshire, to begin exposing P.

destructans and six related fungi to DNA

damaging agents, and they discovered a possible

Achilles’ heel in P. destructans: a

brief exposure to UV-light is lethal to it.

The discovery could lead to treatments for what

is potentially the most catastrophic wildlife

disease of the century.

The fungal disease was first documented in 2006

in eastern North America, New York, and the

fungus has advanced west across the continent,

most recently being detected on the west coast.

Research has identified that there was a single

introduction of P. destructans into

North America in 2006, which has since spread to

31 states, including an apparent long-distance

jump to Washington state.

|

|

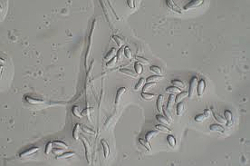

P. destructans |

The fungus has a strict and cool temperature

growth range and therefore can only infect bats

during hibernation.

WNS can result in a 90-percent or greater

mortality in local hibernating bat populations.

Frequent arousal from hibernation, depletion of

fat reserves and dehydration appear to

contribute to mortality in infected bats.

P. destructans has been found

throughout Eurasia and it occasionally causes

mild WNS symptoms; however, no mass mortality

events have been observed in Eurasia. The fungus

has spread in a “bulls eye” pattern in North

America and has only been found in environments

where WNS-infected bats are found, strongly

suggesting that the fungus is not native to

North America.

The study, which was funded by the U.S. Fish and

Wildlife Service, was published in the journal

Nature Communications and is available by

clicking here. |

|

Questions or comments about this

letter?

Click here to e-mail! |

|

|

|

|