|

By Mike Weland

|

| Navy-Marine

Corps Medal of Honor |

On June 13, 1966, 16 United States Recon Marines

and two Navy Corpsmen, led by Staff Sergeant

Jimmie E. Howard, made their way up a

1,500-foot, bare-topped hill called Nui Vu by

the local Vietnamese.

They were one of seven

teams from the 1st Reconnaissance

Battalion, 1st Marine Division, sent

out in what was dubbed Operation Kansas, an

extensive reconnaissance effort designed to find

the headquarters of the 2nd North

Vietnamese Army near the Que Son Valley.

For the next few days, the

Marines of Recon Team 2, on what became known as

Hill 488, dug in and reported enemy movement and

called in successful artillery strikes on

targets of opportunity in an uneventful mission.

On the morning of June 15,

SSGT Howard, despite concerns that the enemy,

who by the accurate artillery fire falling on

them might know they were under observation, and

from where, radioed back to his battalion

commander asking permission to stay one more

night.

Permission was granted.

|

|

Nui Vi,

called Hill 488 by U.S. personnel , was

the site of a battle so fierce those

who've studied it call it a modern-day

Alamo ... except that thanks to the

heroism of one man, American Marines

lived to tell the story. |

Unknown to the Marines on the hill, the North

Vietnamese did know where the observation post

was, and had begun mobilizing an attack force on

June 14.

On the night of June 15, a

nearby Army Special Forces team leading a

Civilian Irregular Defense Group patrol radioed

a warning that they’d spotted a battalion of up

to 250 Vietnamese regulars closing in on Hill

488.

Too late to evacuate, the

men manning the observation post did what they

could to improve their defenses and hunkered

down.

At about

10 p.m., a 20-year-old Marine Lance

Corporal who’d enlisted in the Marines in 1963

and got off to a somewhat shaky start in the

Corps until volunteering for

Vietnam

and then volunteering again to become an elite

Recon Marine, saw the enemy approaching and

fired the first shots of the night from his M14.

The "bush" he shot stood up and collapsed yards

away, the first of many combatants to die that

night.

It wasn’t a battalion, as

anticipated, but a regiment, though the 18 men

on the hill didn’t know it at the time. All they

knew was that they were surrounded by an

aggressive, determined and well-led force that

seemed to have no end.

|

|

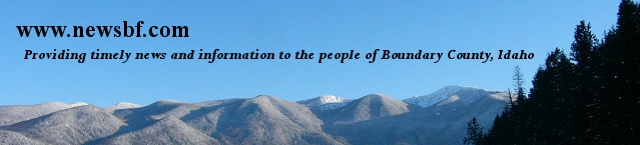

Marine Lance

Corporal Ric Binns (foreground)

and team members Tom Powles, Joseph

Kosoglow and William Norman. |

While Howard manned the radio, reporting on the

action to headquarters, requesting evacuation

and air support, the Lance Corporal, who’d come

up the hill as first team leader, stepped up

again to effectively serve as platoon leader,

taking tactical control of the pitched battle,

gathering his men into a tight defensive

fighting position around a rock outcropping so

as to protect their leader, coordinating with

and relaying orders from Howard, all the while

taking continuous fire.

For the next seven hours,

during which six members of the besieged platoon

were killed and everyone else wounded in the

opening salvos of the battle, Lance Corporal

Ricardo Binns, now of Bonners Ferry, rallied the

survivors, directing fire, passing around

ammunition, tending to the wounded, as enemy

soldiers surrounding their position poured down

a continuous rain of grenades and withering fire

from heavy machine guns, 60mm mortars, AK-47 and

small arms.

Overhead, close air support

aircraft circled helplessly, providing fire

where they could, but unable to do so

effectively as the enemy was too close to the

embattled but tenacious Marines. With flares

parachuting down from the circling planes, those

few recon Marines repelled several coordinated

attacks and relentless and continuous harassing

fire.

|

| An artist's

rendition of the Battle of Hill 488, as

described by Ric Binns, that appeared in

the May, 1968, issue of Readers Digest. |

By early morning, the Marines were running low

on ammunition, some using captured AK-47s to

continue the fight. Out of grenades, they

resorted to throwing rocks and fighting the

enemy at close quarter, with Binns, despite

having been wounded by grenade shrapnel in both

legs and having been machine-gunned across the back,

continuing to rally the men, exposing himself

countless times to enemy fire while bringing the

worst wounded into the least exposed positions

and protecting the bodies of the dead, returning

the taunts of the enemy with audacious taunts of

his own.

A pair of helicopters

attempted to land on the hill at around

3 a.m., but were driven off by heavy

fire. When daylight broke, the Vietnamese, now

vulnerable to air attack, dug in. During a brief

lull in the fighting, a Marine observation

helicopter flown by Major William Goodsell again

attempted to land to get the worst of the

wounded evacuated, but his craft was shot down

and he later died of his injuries. Another

helicopter, offering itself as “bait” to draw

enemy fighters into the open, was also shot

down, killing a crew chief. Two other Marines

aboard helicopters desperately trying to come to

the aid of the beleaguered platoon were also

killed.

|

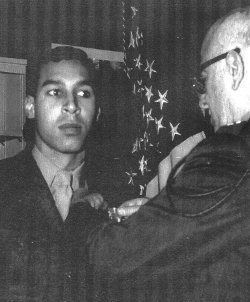

|

Lance

Corporal Ric Binns being awarded the

Navy Cross, the service's second highest

award for valor in combat. |

Just before 10

a.m., June 16, Company C, 1st

Battalion, 5th Marines were landed on

the south face of Hill 488, and they were able

to push back the enemy so that the wounded and

dead Recon Marines could be evacuated. Refusing

medical attention until every member of his team

was accounted for, Binns was the last member of

his team to take his boots off Hill 488.

In the final tally, the 18

men on the hill through that endless night

killed an estimated 200 enemy to the six men

they lost, with Binns credited with at least 30

kills.

In the aftermath of the

battle, Howard was promoted to Gunnery Sergeant

and presented the Medal of Honor. He died in

1993 at the age of 64.

Binns, shuffled off to a

series of hospitals and kept in near solitary

confinement, was one of four members of the

recon platoon to be awarded the Navy Cross, that

service’s second highest award for valor, two of

those posthumously. Thirteen Silver Stars were

awarded the rest of the team, four of them

posthumously. Every member of the team was

awarded the Purple Heart, Binns his second.

|

|

Ric Binns

shaking hands with President Lyndon B.

Johnson during the ceremony at which the

Medal of Honor was conferred on Staff

Sergeant Jimmie Howard August 21, 1967. |

Permanently disabled by the wounds he sustained

on the hill that fateful night, Binns was

medically retired from the Marine Corps in 1971.

Because of his troubles initially adjusting to

the Corps, he was given a general discharge. His

DD-214, probably the most important piece of

paper a military veteran who served honorably

can own, didn’t list his Navy Cross.

In the early 1970s, a young

Marine Corps officer, Robert Adelhelm, studied

the Battle of Hill 488 at Marine Officer’s

Basic

School. He went on to become a Recon

Marine before retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel.

After serving his country, Adelhelm went on to

serve the nation’s veterans, and one of them,

Silver Star recipient Chuck Bosley, had been a

Marine private first class on that fateful night

in 1966. Bosley told him his recollections of

the events on Hill 488, and, intrigued, Adelhelm

began seeking out other members of the platoon,

the officers who led them and all the

documentation he could get his hands on, often

resorting to using the Freedom of Information

Act, convinced that the United States of America

had forgotten one of its true heroes, Ricardo C.

Binns.

|

|

Marine

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Adelhelm,

retired, who studied the Battle of Hill

488 while in officer's school, and who

came to believe that a fellow Marine had

been denied due honor for valor above

and beyond the call of duty. |

“Real heroes are people like Ric Binns,”

Adelhelm, now living in

Jacksonville, Florida,

said. “They have flaws. He wasn’t a perfect

Marine. It’s probably because of that, because

of who he was, that he stood up and took charge,

defying what most people would have seen as

overwhelming odds. I don’t think it unreasonable

that people who know about Hill 488 compare it

to the Battle

of the Alamo, except that

in this battle, American Marines survived. The

more I learned about it, the more convinced I

became

that the only reason they did was because of Ric

Binns. You people have a hero in your midst, and

sadly, very few of you know it.”

What began as a matter of

interest grew to become a mission for the

retired Recon Marine, who is convinced by the

record and by what he’s learned that the Marine

Corps, for whatever reason, deprived a true hero

of the recognition he deserved, the Medal of

Honor. Worse, he said, was the way the Marine

Corps treated a hero after shunting him out of

the service.

“They gave this man a

general discharge,” Adelhelm said. “A Marine who

volunteered for

Vietnam, with

two Purple Hearts and the Navy Cross! As an

executive officer, I processed quite a few

discharges in my time, and I’ve never heard of

the Marine Corps doing anything so callous.”

Binns’ less than ideal

conduct as a garrison Marine, he said, was

partially to blame.

“The Marine Corps rates

every Marine on conduct, and takes away points

for bad marks on your service record,” he said.

“To get an honorable discharge, you have to have

a minimum of four points. Ric had 3.75. In light

of the Navy Cross, that shouldn’t have mattered.

But that medal wasn’t even listed on his

DD-214.”

Because of the less than

honorable discharge, Binns found it hard, once

he was out of the hospital, to find a job. When

he went to VA Hospitals for needed treatment, he

was shuttled to the back of the line.

“Back then, your military

service meant something, and a less than

honorable discharge slammed a lot of doors shut

in your face,” Adelhelm said. “It took him 10

years of fighting a bureaucracy to have his

record corrected and his discharge status

upgraded to ‘Honorable.’ For 10 years, Ric Binns

was denied even the recognition and privilege

that comes with an honorable discharge and

with wearing the Navy Cross.”

A more subtle reason for

what Binns endured, he said, may have been the

times, a period of national unrest as protest

against the Vietnam War set cities across the

country aflame, the color of Ric Binns’ skin and

the fact that Binns refused to die.

“You have to remember the

times,” he said. “In 1966, it was a racially

charged environment. I think it’s safe to say

there were some who didn’t want to put a Medal

of Honor on a face that wasn’t white.”

Just reading the citations

of the medals awarded, he said, makes it clear

that an injustice was done.

“I read all the citations

arising from the battle and there were none that

compared to Binns.’” he said. “If you read

Binns’ Navy Cross citation, it reads like a

Medal of Honor citation.”

More telling yet, he said,

are the very words of Jimmie Howard in his

statement on the battle, written shortly after

he’d come down from Hill 488:

“On

June 16, 1966, as the Platoon Leader

of the 1st Platoon, Company “C”, 1st

Reconnaissance Battalion,” he wrote, “My platoon

was manning an observation post located on Hill

#488. We had been continuously probed by the VC

since 2100 (9

p.m.) the previous day. At

approximately 0100 (1

a.m.) on the 6th, we were

attacked by a well-trained North Vietnamese

unit, which I estimated to be of battalion size

but was later established as a regiment. LCpl

BINNS was the first to see the enemy. He and his

team immediately took the enemy under fire and

dropped back to take their position on the

platoon defensive perimeter. Shortly thereafter,

every member of the platoon was hit, six of

which died instantly or of wounds later.

Insamuch as I was hit and could not walk, I

remained on the radio and directed attack

aircraft and relayed my commands through LCpl

BINNS. Though painfully wounded by shrapnel in

one leg and later in the other he constantly

exposed himself to intense enemy fire, which

came from 50 caliber machine guns, 60 millimeter

mortars, light machine guns, grenades and small

arms. Moving from man to man, he directed their

fire and assisted our corpsmen in caring for the

other wounded. Two grenades exploded near PFC

T.G. POWLES, and in addition to severely

wounding him in the chest, the concussion effect

blinded him. POWLES stood up and would have been

killed had not BINNS, in complete disregard for

his personal safety, stood up and pushed POWLES

to the ground and administered emergency

treatment. As the assault progressed our

effective strength was reduced to seven men. At

this point, LCpl BINNS took it upon himself to

redistribute ammunition of those that were

incapable of using it. This he continued to do

throughout the night and into the late morning,

when a reaction force arrived to relieve us. He

appeared to be everywhere at once. At one point

when the enemy was close they called out,

‘Marines you die within the hour.’ Upon hearing

this, Lcpl BINNS stood up and took them under

fire and shouted back at them. There is no doubt

in my mind that LCpl BINNS’ heroic actions and

indomitable fighting spirit were instrumental in

inspiring our remaining 7 effective men to fight

savagely and hold their position against

overwhelming odds.”

“It’s clear from that

statement,” Adelhelm said, “that Howard believed

Binns merited the Medal of Honor.”

Another factor in his

belief that the honors for the actions of the

brave Recon Marines and Navy Corpsmen on that

hill that night were misappropriated is the

speed at which those medals were conferred.

“Award package,” he wrote

in his recommendation, “was submitted to

Division on June 20th, 4 days after

the battle, and division forwarded the package

to FMF (Fleet Marine Force) Pacific on June 22nd

… LCpl Binns was evacuated after the battle to

Chu Lai hospital on June 16 and was unable to

walk … LCpl Binns was informed on June 16th,

within hours of his evacuation from the battle,

he was going to be awarded the Navy Cross by his

battalion commander … LCpl Binns was transferred

to the DaNang Hospital after being operated on

at Chu Lai Hospital, was eventually transferred

to the Naval Hospital Guam on June 27, 1966, St.

Albans Hospital, NY on August 10, 1966 and

administratively transferred to MB (Marine

Barracks) Brooklyn Navy Yard until his discharge

in November, 1966 … LCpl Binns was not visited

or contacted by any members of his battalion

while in DaNang or the stateside hospital … LCpl

Binns was not debriefed on the patrol nor did he

provide any information regarding the subsequent

award recommendations … There is no evidence to

substantiate witnesses being interviewed at the

battalion or division level prior to the awards

package being forwarded to FMC

Pacific … The manner in which this was handled

raised questions whether the most deserving

received ultimate recognition. The absence of an

internal awards board at either the battalion or

division level precluded any proper evaluation

and vetting. This despite the fact the higher

the proposed award there is usually a lengthy

vetting process to verify all the facts involved

in the recommendation.”

You can read Adelhelm's

full report and find other documentation

regarding his recommendation on his website,

https://sites.google.com/site/jaxsemperfidelissociety/stolen.

The Marine Corps hierarchy

of the time, he fears, had pre-determined which men on that hill would get what awards

even before the battle had ended, and the

highest ranking member would get the highest

honor.

“In the past,” Adelhelm

wrote, “history has shown that heroic behavior in

battle seems more widespread than awards of the

Medal of Honor, and this case is no exception.

There have been cases where an ‘unacceptable’

individual who exhibited extraordinary bravery

may not be recommended and a more ‘acceptable’

individual chosen that has the ‘hero personna’

versus the actual individual who performed the

heroic acts. This, coupled with the unrealistic

‘one-man-per-battle’ limit on the MOH that

exists, ensures that some will not get their

rightful recognition despite any heroic actions

and the impact they had and the outcome of the

situation. In this case, perhaps some at the

battalion and division levels decided a Marine

need to not only be very brave in a given

action, but also be politically acceptable.”

While hard to define or

classify, Ricardo C. Binns isn’t white.

|

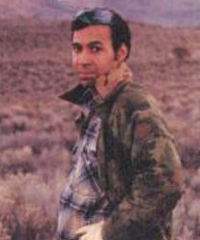

|

Ric Binns,

circa 1990. Now living in Bonners Ferry,

he's changed but little over the ensuing

years. |

“L/Cpl Binns is a Marine of color,” Adelhelm

wrote. “In 1966, social unrest and the turmoil

that plagued the social fabric of our society

pushed individuals in strange directions. He is

a Marine of British West Indian descent whose

ethnicity is enigmatic. His ethnicity has been

changed on various official military documents.

His initial DD-214 form classified him ‘Neg

(negro) despite the fact his initial enlistment

documents stated otherwise. Subsequent DD-214s

did not have a race category; it was replaced

with US Citizen.”

Jimmie Howard was the

epitome of a Marine non-commissioned officer,

tall, straight, a former Marine Corps Drill

Instructor and recipient of the Silver Star and

two Purple Hearts in

Korea, hailing

from the nation’s heartland,

Burlington, Iowa, where he

graduated high school in 1949.

Adelhelm doesn’t begrudge

Jimmie Howard the Medal of Honor, nor does he

insinuate that this decorated Recon Marine

didn’t deserve it … the Medal of Honor, he said,

is a medal conferred by a grateful nation, not

sought by those upon whom the award falls.

The people in charge at the

time, all the way up to President Lyndon B.

Johnson, who linked the clasp of that pale blue

ribbon on only the sixth U.S. Marine to be so

honored for service during the Vietnam War on

August 2, 1967, agreed that Jimmie Howard was

deserving of this nation’s highest honor for his

actions in that battle.

Adelhelm believes that Jimmie Howard and Lance Corporal Ric Binns were

both victims of a bureaucracy more interested in

preserving an image rather than in bestowing

honors for valor where due.

A bit of history gives

grounds for his concerns.

Since the inception of the

Medal of Honor during the Civil War, 3,464 have

been conferred, a disproportionate number of

them during that war because the high standards

associated with the Medal of Honor only came

later. Of that number, 88 have been bestowed on

men of color.

Robert Augustus Sweeney, a

Canadian who emigrated to the U.S. and enlisted

in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, is the

only black man to have been awarded the Medal of

Honor twice, both times for saving the lives of

shipmates. His is a distinction shared by a

total of 19 heroes, all but one white, to be so

honored twice.

In all, 25 men of color

awarded the Medal of Honor were so recognized

for their actions in the Civil War. The only

Medal of Honor conferred by this nation to a

woman also came during the Civil War when

President Andrew Johnson presented it to Dr.

Mary Walker. While she wore her Medal proudly

until she died in 1919, Congress had rescinded

her award in 1917, along with some 900 others.

It wasn't until 58 years later, on June 10,

1977, that her valor was reaffirmed when

President Jimmy Carter, with the approval of

Congress, restored her Medal of Honor.

During the Indian Wars that

followed on the heels of the Civil War, 18

“Buffalo Soldiers” were presented the Medal of

Honor. Citations were brief, "Gallantry in the

fight between Paymaster Wham's escort and

robbers. Mays walked and crawled 2 miles to a

ranch for help," read that presented to Isaiah

Mays, a black Army corporal serving with the 24th

Infantry Regiment in

Arizona.

Six men of color were

presented the Medal of Honor during the Spanish

American War, five “Buffalo Soldiers,” four of

them for action in a single engagement, and one

U.S. Navy sailor, honored for "performing his

duty at the risk of serious scalding at the time

of the blowing out of the manhole gasket on

board the vessel, Penn hauled the fire while

standing on a board thrown across a coal bucket

1 foot above the boiling water which was still

blowing from the boiler."

|

|

The grave of

Army Corporal Freddie Stowers

at Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery,

France. It took 73 years for this nation

to recognize his valor.

|

During World War I, standards were tightened,

and only one black man serving received the

Medal of Honor, but not until 73 years had

passed. Army Corporal Freddie Stowers, serving

in the 93rd Division, “Led his squad

to destroy a group of enemy soldiers and was

leading them to another trench when he was

killed” in 1918.

After his death, Corporal

Stowers was recommended for the Medal of Honor,

but the recommendation was never processed.

Three other black soldiers were also recommended

for Medals of Honor in that war, but were

instead awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

In 1990, at the instigation

of Congress, the Department of the Army

conducted a review and the Stowers

recommendation was uncovered. Subsequently, a

team was dispatched to

France, and

based on their findings, the Army Decorations

Board approved the award of the Medal of Honor,

which President George H.W. Bush presented to

Stower’s surviving sisters, Georgina

and Mary, on April 24, 1991.

During World War II, no

Medals of Honor were bestowed on black men,

though black men comprised nearly a quarter of

the forces this nation sent to fight.

|

|

Vernon Baker,

St. Maries, Idaho, shaking the hand of

President Bill Clinton after receiving

the Medal of Honor, 53 years after his

brave actions on a battlefield in Italy

during World War II. |

Only 53 years later, and after exhaustive

review, were seven African Americans awarded the

Medal of Honor by President Bill Clinton. All

were recipients of the Silver Star for their

wartime service and only one,

St. Maries, Idaho,

resident Vernon Baker, was alive to attend the

ceremony.

The other six were awarded

posthumously.

Two black Army soldiers,

both members of the 24th Infantry

Division, won the Medal of Honor during the

Korean War, both posthumously.

In Vietnam, 20 American

servicemen of color were awarded the Medal of

Honor, including five black Marines, all of them

posthumous, and all awarded for their actions in

saving the lives of fellow Marines by fearlessly

giving up their own, most often by diving on a

grenade.

And all for actions that

took place well after June 15, 1966, when a

young U.S. Marine of color from the mean streets

of the Bronx held a team of 18 men together

through the worst kind of hell against an enemy

force estimated in the hundreds and lived, and

who, in the process, kept a number of the men he

served with alive to come back and tell the

tale.

“Ric Binns, on that night,

epitomized everything this nation defines as

heroic,” Adelhelm said. “That he’s been treated

the way he has is a smear on both the United

States Marine Corps and this nation. At the

least, the Marine Corps owes this man an

apology. At best, the Corps can do what’s right

and give this man the credit he’s due.”

Well familiar with military

bureaucracy, Adelhelm began wading through the

mountains of red tape to correct what he sees as

a stain on his beloved Marine Corps, and, by

default on his nation.

In May, 2010, he submitted

a 10-page recommendation that Binns’ Navy Cross

be upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

He did much more than his

homework. Over the course of years, he compiled

interviews with the surviving members of the

recon unit, verified what he was hearing by

interviewing others who were on the ground and

in the air as headquarters scrambled to salvage

what appeared, at the time, to be a lost cause.

He gained access to 57 taped interviews of the

surviving platoon members and tried his best to

talk to the officers who processed the paperwork

after those 18 men won that battle.

The men on the ground and

in the air, he said, all told the same story …

L/Cpl Ricardo C. Binns was the factor, the one

Marine on that hill who used what little he had

at his disposal to disorient, confuse and

ultimately defeat a tenacious enemy intent on

using superior numbers and overwhelming

firepower to defeat an exposed and lightly armed

enemy. Long after being given up for lost,

Ricardo Binns, by personal example, imbued in

the men the willingness to keep on fighting,

even though he didn’t technically hold the rank

to lead.

At first, Adelhelm ran into

a wall of apathy. Because more than two years

had passed, the recommendation had to have a nod

to proceed from a sitting U.S. Congressman

representing the proposed recipient’s current

home state, in this case,

Idaho. Even as he

submitted his recommendation to Walt Minnick,

Minnick fell in an election.

He submitted the

recommendation to Jim Rische and heard nothing.

Then Raul Labrador came to

office, and the new Congressman gave it his

signature.

The recommendation,

Adelhelm said, is now where it should have been

in the weeks after the Battle of Hill 488, going

through Marine Corps channels.

With Labrador’s

approval, he said, the recommendation is

“getting legs.”

“The Marine Corps now has

the package and will make a decision sometime in

June,” he said.

But even if they give it

their stamp of approval, Adelhelm said, the

request still has a long way to go, and local

support can help.

Those interested in

supporting this effort can best do so, he said,

by encouraging the Idaho Congressional

delegation to see this recommendation through.

Senator Mike Crapo can be

reached by writing him at 239 Dirksen Senate

Building, Washington, DC, 20510, or by calling

(202) 224-6142; Senator Jim Risch, 438 Russell

Senate Building, Washington, DC, 20510, (202)

224-2752, and Congressman Raul Labrador, 1523

Longworth House Building, Washington, DC, 20510,

(202) 225-6611.

If the United States Marine

Corps does right by this hero and recommends

approval, the application gets bumped up through

myriad channels all the way to Commander in

Chief.

If the President of the

United States approves, a ceremony will be set

and the Medal of Honor conferred.

If that happens, Adelhelm

says, a great wrong will be made right.

And Ricardo C. Binns will

again be entitled to do something he's been

denied since his less than honorable discharge

in 1971, don a uniform he still cherishes ...

that of a United States Marine.

|